By Yasmin Carpenter

The concepts of modernity and Eurocentrism lie at the core of the decolonial critique of Western thought. Far from being neutral or universal categories, they describe a historical project that has defined what counts as reason, progress, and humanity from a specifically European standpoint. The decolonial perspective argues that modernity’s celebrated ideals—rationality, science, and progress—cannot be separated from the colonial violence that made them possible.

Modernity as a Colonial Project

In the traditional Western narrative, modernity marks the transition from the medieval to the modern world: a story of emancipation from superstition through the triumph of reason and science. Decolonial thinkers, however, challenge this chronology. They locate the true beginning of modernity not in the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, but in 1492, with the conquest of the Americas and the first global expansion of Europe (Mignolo 2000; Escobar 2003).

This shift in perspective reveals modernity as inseparable from coloniality. The technological, economic, and philosophical developments that Europe presented as internal achievements were, in reality, enabled by conquest, genocide, and the extraction of wealth from colonized territories. As Aníbal Quijano (2000) argues, the “modern world-system” was built through the colonial classification of peoples, territories, and knowledges — a structure that organized the world around a racial and epistemic hierarchy with Europe at its center.

Modernity’s “universal” values, therefore, were never universal at all: they were local experiences made global by force (Grosfoguel 2008). The idea of Europe as the measure of civilization and rationality was sustained by what Walter Mignolo calls the “rhetoric of salvation” and the “logic of coloniality”: a discourse that claimed to civilize while destroying the worlds it encountered (Mignolo 2007).

On Eurocentrism

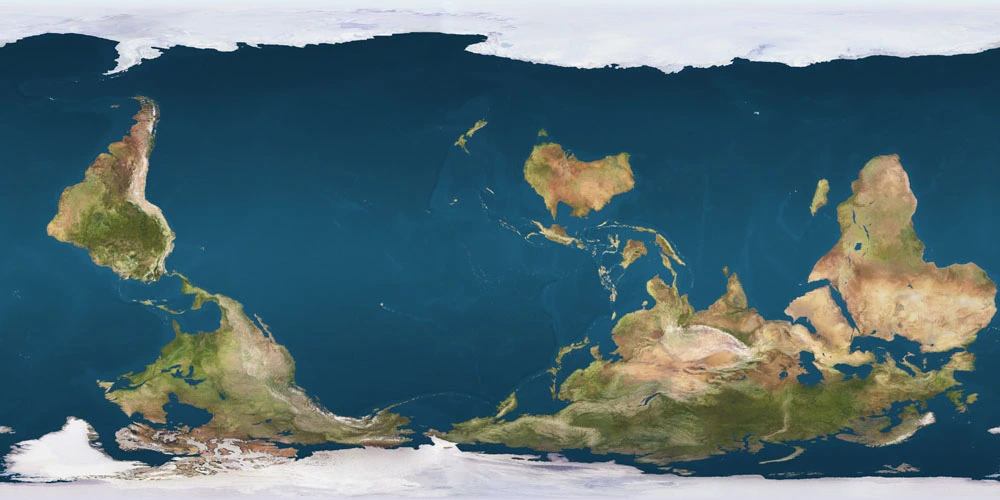

Eurocentrism is the epistemological expression of this history. It refers to the worldview that places Europe—and later the Euro-American world—as the center of knowledge, culture, and humanity. Eurocentrism presents its categories as neutral and objective, concealing the power relations that sustain them. It operates through what Castro-Gomez (2005) calls the zero point hubris — the illusion that knowledge can be produced from a view “from nowhere,” detached from any geopolitical or body-political location, and therefore, made objective and universally applicable.

In practice, Eurocentrism constructs a global order of meaning where the West is synonymous with universality, and all other cultures are positioned as particular, local, or primitive. Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2002) refers to this as the “monoculture of modern science”, which systematically produces “epistemic absences”: entire worlds of knowledge rendered invisible or inferior. The result is what he calls the sociology of absences—a condition in which non-Western ways of knowing exist only as residues, myths, or folklore.

Eurocentrism also defines modern time. Dipesh Chakrabarty (2000) notes that the linear, progressive temporality of modernity—where Europe is seen as the advanced future and the rest of the world as its past—creates a global hierarchy of historicity. Within this temporal order, Europe becomes not only the origin of progress but also the destiny of all societies.

Critique and Reorientation

Decolonial theory seeks to provincialize Europe—to reveal it as one historical location among many, not the universal source of meaning. This reorientation does not deny the importance of European thought but situates it within a broader planetary field of knowledge (Chakrabarty 2000; Mignolo 2007).

By exposing the colonial foundations of modernity, decolonial thinkers open space for what Santos (2014) calls an ecology of knowledges: a coexistence of epistemologies that recognize the plurality of human experience. However, unlike pluralism within modernity, this perspective requires a break with its foundational myth of universality.

To critique Eurocentrism, therefore, is not merely to “include” the excluded within the same frame of reference. It is to challenge the very architecture of that frame—the assumption that knowledge, reason, and progress flow from a single historical center. Decoloniality thus calls for a radical epistemic shift: to think from the borders rather than about them.

—

This entry is part of an ongoing series exploring the core concepts of decolonial thought within the DCC Encyclopedia. To continue reading, click here to explore related entries on coloniality of power, coloniality of knowledge, and decoloniality.

—

References

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Escobar, Arturo. Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise: The Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program. Cultural Studies, 2003.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. “Transmodernity, Border Thinking, and Global Coloniality.” Review 31(3), 2008.

- Mignolo, Walter D. “Desobediencia Epistémica: La Opción Descolonial.” Revista Gragoatá, 2007.

- Mignolo, Walter D. Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking.Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 2000.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. “Para uma Sociologia das Ausências e uma Sociologia das Emergências.” Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 63, 2002.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Routledge, 2014.