By Yasmin Carpenter

The notions of coloniality of knowledge and coloniality of power are among the most influential contributions of Latin American decolonial thought. Developed by Aníbal Quijano and expanded by Walter Mignolo, Ramón Grosfoguel, and others, they describe how colonial domination operates not only through political and economic control but also through the control of knowledge and meaning. These two forms of coloniality are inseparable: knowledge legitimates power, and power institutionalizes knowledge. Together, they sustain the global hierarchies that define the modern world.

The Coloniality of Power

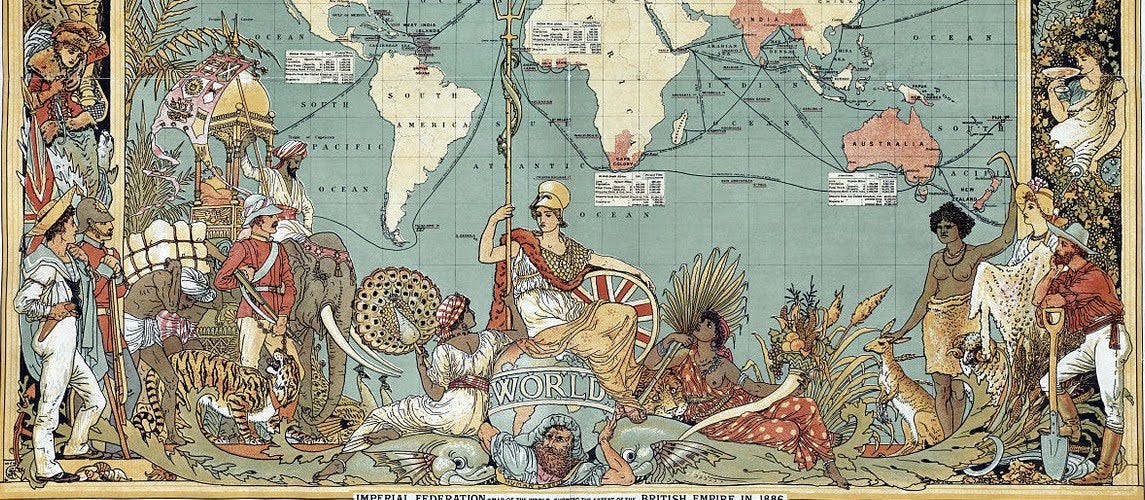

Aníbal Quijano (2000) introduced the concept of coloniality of power to explain how colonial domination outlived formal colonialism. The European conquest of the Americas inaugurated a new world order that organized labor, authority, and social relations through a racial classification of the world’s population. This racialized system assigned value and humanity along a hierarchy—with European, white, Christian men at the top and Indigenous, African, and colonized peoples at the bottom.

This structure, according to Quijano, became constitutive of modernity itself. The global capitalist economy, born out of the colonial encounter, was inseparable from the production of racial difference. The colonized were not merely exploited; they were made to embody a position of inferiority that justified their exploitation. Thus, the coloniality of power does not end with historical colonialism: it persists as a pattern of power that structures the modern world-system through race, labor, and capital.

The Coloniality of Knowledge

The coloniality of knowledge is the epistemological counterpart to this structure. It refers to the ways in which Western modernity imposed its own forms of knowing as the only valid ones, declaring other epistemologies—Indigenous, African, Asian, popular, spiritual—as irrational, mythological, or pre-modern (Mignolo 2000; Santos 2002).

As Mignolo (2009) argues, modern Western epistemology claims a “view from nowhere” — a universal, objective standpoint that conceals its own geopolitics of enunciation. This illusion of neutrality enables the West to define itself as the bearer of truth and progress, while relegating other knowledges to the realm of superstition or tradition. The process constitutes what Boaventura de Sousa Santos (1998) calls an epistemicide: the systematic erasure of knowledge systems that do not conform to the scientific rationality of modern Europe.

Knowledge as an Instrument of Power

The link between these two forms of coloniality lies primarily in the way knowledge legitimates power. Colonial domination was not maintained solely through force; it required a moral and rational justification that made the imposed hierarchy appear natural and inevitable. The ideas formed by European rationality provided precisely that. By presenting its own views and ideas as neutral and universal, Western knowledge justified colonialism as a civilizing mission.

This dynamic also worked in reverse: power institutionalized knowledge. The colonial state, the Church, and the emerging universities of the modern era became the key sites for producing and reproducing Eurocentric epistemologies. As Grosfoguel (2008) observes, modernity’s claim to universality was made possible by its control of both “the means of destruction and the means of signification.” The authority to name, classify, and represent the world was as central to colonial rule as the authority to conquer it.

Thus, the coloniality of knowledge and the coloniality of power form a single system of domination: one that controls both what the world is and who is allowed to know it.

—

This entry is part of an ongoing series exploring the core concepts of decolonial thought within the DCC Encyclopedia. To continue reading, click here to explore related entries on coloniality of power, coloniality of knowledge, and decoloniality.

—

References

- Escobar, Arturo. Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise: The Latin American Modernity/Coloniality Research Program. Cultural Studies, 2003.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. “Transmodernity, Border Thinking, and Global Coloniality.” Review 31(3), 2008.

- Mignolo, Walter D. Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking.Princeton University Press, 2000.

- Mignolo, Walter D. “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option.” Transmodernity, 2011.

- Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 2000.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. “Para uma Sociologia das Ausências e uma Sociologia das Emergências.” Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 63, 2002.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide. Routledge, 2014.