By DCC Team

Surplus populations are people capitalism no longer needs for work or consumption. They aren’t an accident but a built-in feature of the system, growing “in the direct ratio of its own energy and extent” (Marx 1976:782). These populations embody capitalism’s contradictions, existing as both the byproducts of economic growth and the human detritus discarded when no longer profitable. Inspired by the work of the late Mike Davis, many today believe that surplus populations might never be reintroduced into the global economy.

Machines, and Surplus Humanity

Capital, in Marx’s view, isn’t just money or machines—it’s a way of organising society around production and profit. It’s a social relation between classes, built around control and exploitation in the production process. Specifically, it’s wealth that grows by extracting value from workers.

Capital is money or resources that are used to make more money. But what makes it powerful is that it’s based on a relationship: capitalists (the owners) control the tools, factories, and raw materials, while workers have to sell their labor to survive. It’s a social relationship where capitalists (the owners) control resources, and most people—because they’ve been dispossessed of land, tools, or any other means of surviving on their own—are forced to work for a wage to live.

One major result of the accumulation of capital is the creation of surplus populations—people who have been pushed out of the economy or left behind by it. Today, these are not just the unemployed or the laid-off factory workers. As Michael Denning reminds us, surplus populations include people who have never been offered a job in the first place: the “wageless” who struggle to survive without regular work, income, or even the hope of getting a job. There is nothing accidental about surplus populations because Capitalism can never offer everybody a job.

Capitalists make their profit from the value workers create. Workers are paid a wage, but the value of what they produce is usually higher than what they’re paid. That extra value is called surplus value, and it’s where profit comes from. Capital, in Marx’s view, isn’t just money or machines—it’s a system built around control, profit, and inequality. As capital grows—what Marx calls capital accumulation—it doesn’t just lead to more factories and more goods. It also changes how work is done and who gets included or excluded from the production process. During his own time Marx believed this was the creation of surplus populations. These are workers who are no longer needed in the production process. They might be unemployed, working part-time, or stuck in low-wage jobs with no stability.

Marx believed that this wasn’t just a temporary issue or a sign that the system is broken. It’s actually how capitalism is designed to work. As production grows, three things usually happen: capital increases, businesses produce more, and technology makes workers more productive. But instead of creating more secure jobs, these changes often lead to fewer workers being needed. So, at the same time that capitalism is expanding, it’s also pushing some workers out—making them “superfluous,” or no longer necessary for production.

Marx called this a law of population under capitalism. This surplus group of workers becomes what he called the industrial reserve army—a group of people who can be hired when needed and let go when not. They help keep wages low and make workers more obedient, because there are always others ready to take their place.

This is connected to another pattern Marx noticed: over time, capitalists tend to spend more money on machines and technology (what he called constant capital) and less on wages for workers (variable capital). This means fewer people are needed to do the same amount of work. But there’s a catch—only workers, not machines, create surplus value. So even though capitalists try to replace workers with machines, they can’t fully get rid of labor without hurting their own profits. This creates a constant tension in the system.

This was how Marx was trying to explain what economists in his time were calling the “residuum” of metropolises like London and Manchester that used to terrify the middle class. In 19th-century Britain, Marx observed that women and children were used for backbreaking labour in mines, not because machines were unavailable, but because human bodies were cheaper. The investment in constant capital meant that wages were depressed. In some cases, even where machines existed, they often went unused if the cost-benefit analysis favoured cheap, expendable labour.

As Victor Lund Shamas puts it:

“The naked, hysterical “wretches” of the Global North no longer toil in physically grueling, gruesome circumstances—they are more likely to be warehoused in a psychiatric ward or jailhouse, or work in a call center at the bottom of the “service” sector—but that is largely because capitalism has transported these forms of production elsewhere.”

To deal with this, capitalism has developed strategies to lower labor costs without relying only on machines. Two common strategies are:

(a) moving production to countries with cheaper labor, instead of keeping factories in places where wages are high, and

(b) using migrant workers to fill low-paying or unstable jobs that can’t be outsourced—like construction or service work.

These strategies don’t just save money—they also create divisions within the working class. Migrant workers and racialised minorities are often blamed for “taking jobs,” even though they’re usually paid less and have fewer rights. This divide and rule tactic helps capitalists keep wages down and stop workers from uniting.

Even in Marx’s time, migrants and oppressed groups were given the hardest jobs and used to weaken solidarity among workers. This pattern has continued throughout the history of capitalism. It allows the system to keep growing while keeping labor cheap and divided.

Capitalism’s Permanent Surplus Populations?

In Africa, ILO estimates imply that the vast majority of workers in the world are “informal workers”, groups hustling to get by.

Is this a temporary thing? For Marx, surplus populations—what he termed the “industrial reserve army”—were a necessary component of capitalism, used to discipline the working class, depress wages, and maintain capitalist control. He feared that these surplus groups, existing outside the circuits of production, could be more susceptible to reactionary forces than to revolutionary ones. But overall, as he saw capitalism developed, he thought that it was the working class – not surplus populations – who had a world to win. Today, of course, most of Marx’s industrial proleteriat toils away in factories in Vietnam, Bangladesh and China. The problem however is that while the majority of workers in manufacturing are in the global south, the majority of workers in the world are not industrial workers. There exists what the late Mike Davis called the “outcast proletariat”, estimated to be around 1.5 Billion who are locked out of formal work. This isnt a temporary reserve army, but a permanent in our planet of slums.

Historically, political economists believed that surplus populations—what they called the residuum or redundant classes—posed a threat to social order only if they remained permanently outside the labour market. As long as capital continued to accumulate and grow somewhere, these populations could be reabsorbed through cycles of economic expansion.

Today, that belief is unraveling. In an era of globalisation, neoliberalism, and automation, capitalism no longer needs huge parts of the population for work or consumption. Saskia Sassen describes this as “expulsion”—the active removal of people from circuits of economic value. Unlike the traditional “industrial reserve army” that could be called upon during economic booms, many surplus populations today are permanently outside the labor market, rendered disposable.

Marx once said that, because of the contradictions of capitalism, the capitalist class is “like the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the netherworld whom he has called up by his spells.” Marx’s sorcerer analogy is eerily prescient today—not just in economics but in global politics. The capitalist state, much like the sorcerer, has unleashed forces it can no longer control. Historically, surplus populations were managed through labor markets, welfare systems, and, when necessary, repression. They were never the majority. But as surplus populations expand and states hollow out under neoliberalism, these traditional forms of control are breaking down.

Political economists of the 19th century, like Malthus, feared that surplus populations could overwhelm the “respectable classes” and destabilise bourgeois society. Yet, they believed that as long as capital accumulated, these groups could be absorbed or at least pacified. Even socialists like Marx and Gramsci viewed mass unemployment and reactionary movements as temporary disruptions rather than permanent features. At the end of the day, the working class would unite and usher in an era of communism.

That optimism of working class triumph is now in crisis. In places like Haiti and Sudan, the state is disintegrating before our eyes. Paramilitaries—once non-state actors operating in the shadows—now openly challenge and, in some cases, supplant state authority. The “deterritorialization” of state violence, where control fragments into multiple competing forces, signals a breakdown in the state’s monopoly on violence. These were forces made up of surplus populations who were used by ruling elites to police other surplus populations. Now they want power themselves, and they have taken over entire cities.

Even in the Global North, the colonial boomerang has returned. The tools of control once used to manage colonial subjects are now being repurposed domestically. Militarised police forces, drones , surveillance systems, and carceral institutions don’t just target migrants, they target surplus populations within Western borders—immigrants, racial minorities, the surplus poor—mirroring colonial forms of governance.

Surplus Geographies: Warehousing Humanity

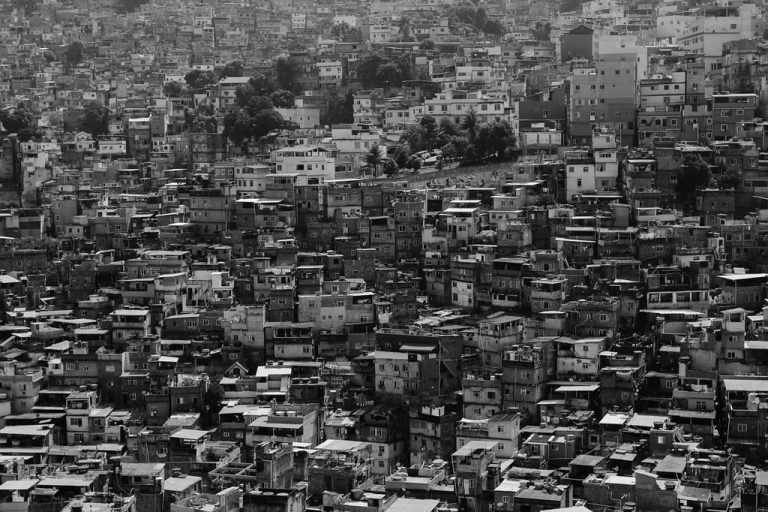

Surplus populations are not scattered randomly; they are concentrated in specific geographies—slums, refugee camps, prisons, and borderlands. Mike Davis, in Planet of Slums, describes how billions now live in informal settlements, cut off from stable employment, healthcare, and political rights. These spaces function as warehouses for surplus humanity—zones of abandonment where people are contained but not integrated.

Borders have become another critical site for managing surplus life. Fortress Europe, the US-Mexico border, and Australia’s offshore detention centres exemplify how states externalise migration control, turning distant territories into holding zones for the world’s displaced. The Rapid Support Forces in Sudan, a key belligerent in the current counter-revolutionary war was once funded by the EU to stop migrants moving north. The 2016 EU-Turkey deal, for example, effectively outsourced the management of Syrian refugees, paying Turkey to prevent migrants from reaching European soil.

These spaces—prisons, camps, slums—are not accidental. They are integral to the global management of surplus populations. They serve as pressure valves, containing social tensions while preventing the overflow of marginalised populations into the spaces of the “respectable” classes. But for how long?

Conclusion

The capitalist system has conjured forces it can no longer control—vast surplus populations, ecological collapse, and political fragmentation. Marx’s sorcerer metaphor remains apt: the system has unleashed contradictions that threaten its own survival.

But unlike Marx’s era, where optimism about systemic transformation ran high, today’s world feels caught between stagnation and decay. The surplus populations grow, but without a clear path forward. The challenge is immense: how to transform wageless life, ecological ruin, and political disintegration into the raw materials for a post-capitalist world.

Surplus populations, long dismissed as passive victims, may yet become the catalysts for a world beyond capitalism—a world where neither people nor the planet are treated as disposable. If they don’t, we may very well be in trouble.

Sources

Benanav, Aaron. “Demography and Dispossession: Explaining the Growth of the Global Informal Workforce, 1950-2000.” Social Science History, vol. 43, no. 4, 2019, pp. 679–703, https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2019.34.

Davis, Mike. Planet of Slums. London Verso, 2006.

Schmitt, Richard. Introduction to Marx and Engels : A Critical Reconstruction. London, Routledge, 2018.

Shammas, Victor Lund. “Capitalism’s Necessary Surplus Population.” Dr. Victor Lund Shammas, 25 Oct. 2019, www.victorshammas.com/blog/2019/10/25/capitals-necessary-surplus-populations. Accessed 25 Mar. 2025.